“Once I start eating, I can’t stop.”

If you’ve ever said something like this (and most people have), then you’re probably familiar with binge eating.

You’re also likely aware of how binge eating can set you back a step or two on your way to achieving your health and fitness goals.

If you’re frustrated by your inability to break your binging habit, this article is for you.

In it, you’ll learn how to stop binge eating using 10 science-backed strategies.

What Is Binge Eating?

Binge eating is a behavior marked by eating large amounts of food quickly.

There are two types of “binge eaters.”

On the one hand, some people occasionally binge without impacting their health. These people often offset their binges by exercising and being more restrained with their diet for the remainder of the time.

In other words, these people are susceptible to overindulging from time to time, often on special occasions such as birthdays, holidays, or while dining in a restaurant, but understand that they have to make up for it in other ways if they want to stay healthy.

On the other hand, some binge more regularly (at least once per week for 3 months) and experience a loss of control over the amount and type of food they eat, feeling ashamed and depressed when they finish. They also don’t compensate for the binges by eating fewer calories at other times or exercising.

These people are likely suffering from binge eating disorder, which is the most common eating disorder in the US and is associated with several conditions that have a detrimental effect on health, including depression, poor cardiometabolic health, strained relationships, chronic pain, obesity, and diabetes.

If you’re seeking help for binge eating disorder, you should speak to your doctor to discuss the best course of treatment.

If you’re in the first camp, however, you don’t need medical help. Instead, you can curb your episodic gluttony using a few simple tips (more on the specifics soon).

What Causes Binge Eating?

Humans are hardwired to love the taste of fat, salt, and sugar.

Calorie-dense, fatty foods gave our ancient ancestors the energy reserves needed to survive food shortages and famines. Salt increases water retention, helping us avoid dehydration. Our sweet tooth led us to sugary berries that were likely edible and away from bitter ones that were likely poisonous.

We’re also hardwired to desire a variety of foods because the more types we eat, the more likely we are to get all the essential vitamins and minerals we need to stay healthy.

Our natural preferences for these flavors and variety in our diets were once valuable tools for staying alive, steering us toward foods that best meet our energy and nutritional needs.

Rapid lifestyle and food availability changes have turned these instincts against us, though. We no longer stalk the plains for dinner—we roam the aisles of the supermarket, faced with an endless variety of high-calorie indulgences.

Unfortunately, our instincts haven’t adapted to the excesses of modern living, which is why we can’t count on them to maintain a healthy body weight—it requires conscious effort.

The good news is that controlling our urges isn’t that hard. All you need are pointers that help you work with your inborn programming, not against it . . .

How to Stop Binge Eating

Whether you want to know how to stop binge eating in general, how to stop binge eating at night, or how to stop binge eating when bored, the following tips will help.

1. Avoid restrictive diets.

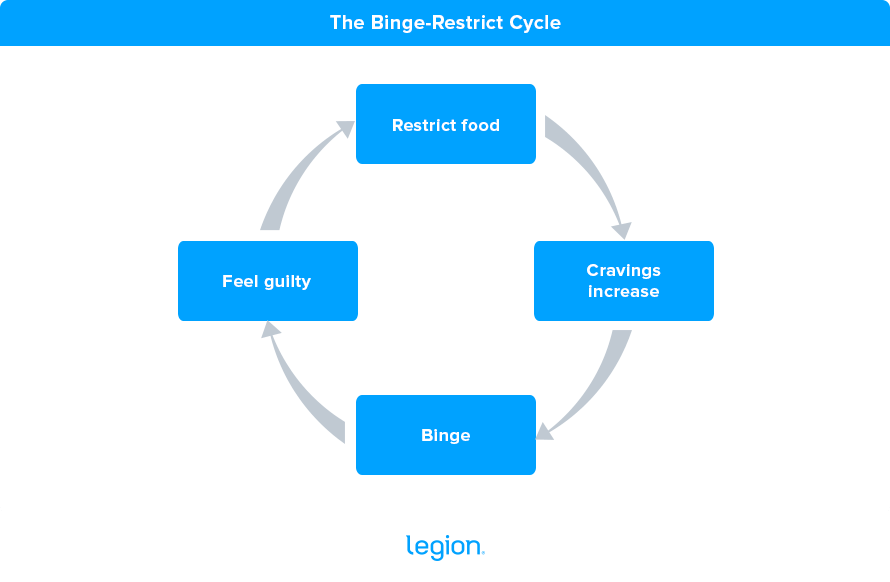

Diets that severely restrict calories or certain foods or food groups can trigger binge eating by sending you into a tailspin commonly referred to as the binge-restrict cycle.

In the binge-restrict cycle, restricting foods causes cravings to increase. When you indulge those cravings, you feel guilty, which you atone for by doubling down on your diet, beginning the cycle anew:

A better option is to follow a flexible dieting approach that allows you to eat all foods while emphasizing whole, unprocessed, nutritious foods, such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean meats, fish, dairy, pulses, nuts, seeds, legumes, and plant oils.

Learn more about flexible dieting here:

How to Get the Body You Want With Flexible Dieting

(Or if you aren’t sure if flexible dieting is right for you or if another diet might be a better fit for your circumstances and goals, take the Legion Diet Quiz! In less than a minute, it’ll tell you exactly what diet is right for you. Click here to check it out.)

2. Don’t skip meals.

Several popular diets, including the OMAD diet, 5:2 diet, and intermittent fasting, involve dispensing with a regular eating pattern to spend extended periods fasting.

Some people like these diets because they condense your daily calories into fewer meals, allowing you to eat larger portions while maintaining or losing weight.

For others, however, fasting gives way to binging once the feeding window “opens.”

The solution is simple: Avoid diets that encourage you to skip meals and instead follow an eating plan that involves breakfast, lunch, dinner, and snacks. Research shows those who follow this strategy are less likely to surrender to the temptation to binge.

3. Keep tempting foods out of sight.

The more you have your favorite foods around you, the more likely you are to eat them.

If every time you feel the slightest hunger, something tasty is nearby, it’s going to take serious willpower to avoid overeating. And when you have to say no 10 times an hour to all your favorite fare, eventually you say yes. And yes. And yes . . .

To avoid this pitfall, make tempting foods more difficult to access (banishing them to the back of a hard-to-reach cabinet works well).

4. Fill up on fewer calories.

Generally speaking, we eat the same amount, or volume, of food every day, and it’s the absolute volume of food eaten that makes us feel full—not the number of calories contained in it (to an extent—calorie density and macronutrient composition do matter as well).

That’s why you could take all the food you usually eat in a day, double its calorie content, and still have no trouble finishing it all.

Fortunately, this principle cuts the other way, too.

For example, if you eat a quarter-pounder when you’re accustomed to eating a half-pound hamburger, you’ll probably still feel hungry when you finish.

If, however, you pad out the smaller burger with lettuce, tomato, and onion so that it equals the volume of the larger sandwich, you’ll find the smaller burger about as filling, despite containing far fewer calories.

Technically, filling up on fewer calories doesn’t prevent you from binging, but it does limit how much you can eat and help you eradicate the feeling of guilt that often accompanies a high-calorie binge.

5. Start exercising.

Studies show that regular exercise—whether weightlifting, cardio, or simply walking—can help you stop binge eating.

For example, in one study conducted by scientists at the University of Pittsburgh, 81% of women who walked 3-to-5 times per week for 6 months stopped binge eating.

Furthermore, exercise (particularly strength training) boosts self-esteem. This is significant because low self-esteem is strongly associated with binge eating. Thus, improving self-esteem may make you less likely to binge in the future.

(And if you’re looking for a strength training program that’s helped thousands of people get in the best shape of their lives, check out my fitness books for men and women, Bigger Leaner Stronger or Thinner Leaner Stronger.)

6. Drink enough water.

Drinking water is a simple way to quell hunger, which means it can also help to dampen the urge to binge.

For example, in one study conducted by scientists at Virginia Tech, people who drank 17 ounces of water before eating consumed 13% fewer calories than those who drank nothing.

In another study published in the journal Obesity (Silver Spring), researchers found that those who drank a 17-ounce glass of water ate up to 111 fewer calories in their next meal.

And in yet another study conducted by scientists at the University of South Carolina, researchers found that people who drink around 50 ounces of water a day eat almost 200 fewer calories per day than people who drink less.

So, next time hunger strikes, drink some water first—it may curb your appetite and prevent you from overeating. And if plane water is too vanilla for you, low- or no-calorie beverages like tea, flavored water, and coffee also work (just make sure you keep your caffeine intake under control).

7. Be present.

Many people mindlessly binge because they don’t concentrate on how much they eat.

(That’s why studies show that people who eat while watching TV tend to overeat and be overweight.)

An excellent way to combat distractedness at meal times is mindful eating, a technique that aims to help you gain control of your eating habits and improve your relationship with food.

Mindful eating involves . . .

- Eating slowly and focusing on every bite

- Paying attention to your hunger cues and only eating to satiety

- Concentrating on things such as the taste, texture, smell, and appearance of your food, as well as how it sounds as you move it in your hands or chew it in your mouth

- Approaching food as if it’s the first time you’ve ever tasted it and letting go of any past experiences you may have had with an ingredient

While this may sound a little “woo woo,” several studies show that mindful eating helps people binge less regularly.

Next time you sit down to eat, turn the TV off, put your phone down, and spend some time thinking about the food you’re eating.

8. Pre-plate your meals.

If you have a habit of eating several helpings during each meal or eating directly out of the box or container your food came in, you’re going to have trouble regulating your food intake.

To remedy this issue, only prepare enough for one portion per meal and put all of the food you plan on eating on your plate (instead of going back for seconds and thirds).

9. Reduce stress.

Many people find that the more stressed they feel, the more likely they are to binge.

One potential reason for this is that stress can prevent you from recognizing when you’re hungry or full.

Thus, one way to minimize the risk of binging is to reduce your stress levels.

Some good ways to do this include:

- Listening to classical music: Studies show that classical music sharpens your mind, engages your emotions, lowers blood pressure, lessens physical pain and depression, and helps you sleep better.

- Consuming less media: Research shows that exposing yourself to a constant barrage of news increases stress levels. Capping your media consumption to 15-to-29 minutes per day should significantly lower your stress.

- Spending less time with tech: Research shows that the more people use and feel tied to their computers and cell phones, the more stressed they feel. In fact, overuse of technology has even been linked with various symptoms of poor mental health, like depression.

- Spending more time with people: Spending time with people, especially your nearest and dearest, is one of the best ways to settle your stress and extinguish your anxiety.

- Practicing yoga: Research shows that yoga not only lowers stress, it may also reduce the incidence of binge eating.

10. Eat more protein.

One of the primary obstacles people encounter when trying to prevent binging is hunger. Eating a high-protein diet is an excellent way to counter this.

Specifically, research shows that increasing protein intake decreases appetite through several mechanisms, including favorably altering hormones related to hunger and fullness.

This satiating effect applies to a high-protein diet in general and individual meals as well: research shows that high-protein meals are more satiating than high-fat meals, which means you feel satisfied longer, making you less likely to binge.

A good rule of thumb is to eat 1 gram of protein per pound of body weight per day.

(And again, if you’d like even more specific advice about how much of each macronutrient, how many calories, and which foods you should eat to reach your health and fitness goals, take the Legion Diet Quiz.)

What to Do After Binge Eating

Even if you do all of the above, there’ll still be times when you overindulge. For many people, this is accompanied by regret, mainly because they think their dietary indiscretions are thwarting their ability to reach their health and fitness goals.

When you stumble (and you will), the first step is to show yourself the same compassion and forgiveness you’d show a friend. A response like this to frustration and failure will help you accept responsibility for your misstep and steam ahead, unfazed.

It also bears remembering that any “damage” you cause by overeating probably isn’t as bad as you think. Studies show that you don’t gain as much fat from a day of overeating as you might think.

The next step is to get back on course, ideally right away.

Practicing the tips in this article as consistently as possible will help them become second nature. The more you do them, the more unconscious they’ll become, and the less often you’ll binge.

FAQ #1: How do I stop binge eating?

If you eat large amounts of food quickly at least once per week for 3 months, experience a loss of control over the amount and type of food you eat, and feel ashamed or depressed when you finish, you may have binge eating disorder.

If this is the case for you, speak to your doctor about the best course of action.

If you don’t suffer the above symptoms and instead find you occasionally overeat without it becoming detrimental to your physical or mental health, follow the steps in this article.

FAQ #2: What should I do if I can’t stop binge eating?

If you follow the advice in this article and still find you regularly overeat, speak to your doctor to understand if there’s an underlying cause for your appetite and the best course of treatment to prevent it in the future.

FAQ #3: How can I stop binging at night?

You don’t have to do anything special to stop night binge eating. Following the steps in this article should prevent binge eating at any time of day.

That said, if you find your hunger seems particularly out of control before bedtime, try snacking on high-protein foods such as greek yogurt, Skyr, or cottage cheese, or drink a protein shake.

(And if you want a clean, convenient, and delicious source of protein, try Whey+ protein powder or Casein+ protein powder. Or if you aren’t sure if Whey+ or Casein+ is right for you, take the Legion Supplement Finder Quiz! In less than a minute, you’ll know exactly what supplements are right for you. Click here to check it out.)

+ Scientific References

- Iqbal, A., & Rehman, A. (2022). Binge Eating Disorder. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551700/

- Brownley, K. A., Berkman, N. D., Peat, C. M., Lohr, K. N., Cullen, K. E., Bann, C. M., & Bulik, C. M. (2016). Binge-Eating Disorder in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 165(6), 409. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-2455

- Javaras, K. N., Pope, H. G., Lalonde, J. K., Roberts, J. L., Nillni, Y. I., Laird, N. M., Bulik, C. M., Crow, S. J., McElroy, S. L., Walsh, B. T., Tsuang, M. T., Rosenthal, N. R., & Hudson, J. I. (2008). Co-occurrence of binge eating disorder with psychiatric and medical disorders. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69(2), 266–273. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.V69N0213

- Leone, A., Bedogni, G., Ponissi, V., Battezzati, A., Beggio, V., Magni, P., Ruscica, M., & Bertoli, S. (2016). Contribution of binge eating behaviour to cardiometabolic risk factors in subjects starting a weight loss or maintenance programme. British Journal of Nutrition, 116(11), 1984–1992. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114516004141

- Kessler, R. C., Shahly, V., Hudson, J. I., Supina, D., Berglund, P. A., Chiu, W. T., Gruber, M., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Andrade, L. H., Benjet, C., Bruffaerts, R., De Girolamo, G., De Graaf, R., Florescu, S. E., Haro, J. M., Murphy, S. D., Posada-Villa, J., Scott, K., & Xavier, M. (2014). A comparative analysis of role attainment and impairment in binge-eating disorder and bulimia nervosa: results from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 23(1), 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796013000516

- Whisman, M. A., Dementyeva, A., Baucom, D. H., & Bulik, C. M. (2012). Marital functioning and binge eating disorder in married women. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 45(3), 385–389. https://doi.org/10.1002/EAT.20935

- Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P. A., Chiu, W. T., Deitz, A. C., Hudson, J. I., Shahly, V., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Angermeyer, M. C., Benjet, C., Bruffaerts, R., De Girolamo, G., De Graaf, R., Maria Haro, J., Kovess-Masfety, V., O’Neill, S., Posada-Villa, J., Sasu, C., Scott, K., … Xavier, M. (2013). The prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Biological Psychiatry, 73(9), 904–914. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BIOPSYCH.2012.11.020

- Hudson, J. I., Lalonde, J. K., Coit, C. E., Tsuang, M. T., McElroy, S. L., Crow, S. J., Bulik, C. M., Hudson, M. S., Yanovski, J. A., Rosenthal, N. R., & Pope, H. G. (2010). Longitudinal study of the diagnosis of components of the metabolic syndrome in individuals with binge-eating disorder. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 91(6), 1568–1573. https://doi.org/10.3945/AJCN.2010.29203

- Raevuori, A., Suokas, J., Haukka, J., Gissler, M., Linna, M., Grainger, M., & Suvisaari, J. (2015). Highly increased risk of type 2 diabetes in patients with binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(6), 555–562. https://doi.org/10.1002/EAT.22334

- Church, T. S., Thomas, D. M., Tudor-Locke, C., Katzmarzyk, P. T., Earnest, C. P., Rodarte, R. Q., Martin, C. K., Blair, S. N., & Bouchard, C. (2011). Trends over 5 Decades in U.S. Occupation-Related Physical Activity and Their Associations with Obesity. PLOS ONE, 6(5), e19657. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0019657

- Peters, J. C., Wyatt, H. R., Donahoo, W. T., & Hill, J. O. (2002). From instinct to intellect: the challenge of maintaining healthy weight in the modern world. Obesity Reviews : An Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 3(2), 69–74. https://doi.org/10.1046/J.1467-789X.2002.00059.X

- Polivy, J., Coleman, J., & Herman, C. P. (2005). The effect of deprivation on food cravings and eating behavior in restrained and unrestrained eaters. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 38(4), 301–309. https://doi.org/10.1002/EAT.20195

- Burton, A. L., & Abbott, M. J. (2017). Conceptualising Binge Eating: A Review of the Theoretical and Empirical Literature. Behaviour Change, 34(3), 168–198. https://doi.org/10.1017/BEC.2017.12

- Stice, E., Davis, K., Miller, N. P., & Marti, C. N. (2008). Fasting Increases Risk for Onset of Binge Eating and Bulimic Pathology: A 5-Year Prospective Study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117(4), 941. https://doi.org/10.1037/A0013644

- Zendegui, E. A., West, J. A., & Zandberg, L. J. (2014). Binge eating frequency and regular eating adherence: the role of eating pattern in cognitive behavioral guided self-help. Eating Behaviors, 15(2), 241–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EATBEH.2014.03.002

- Wansink, B., & Deshpande, R. (n.d.). “Out of Sight, out of Mind”: Pantry Stockpiling and Brand-Usage Frequency on JSTOR. Retrieved November 16, 2022, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/40216327

- Wooley, S. C. (1972). Physiologic versus cognitive factors in short term food regulation in the obese and nonobese. Psychosomatic Medicine, 34(1), 62–68. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-197201000-00007

- Galasso, L., Montaruli, A., Jankowski, K. S., Bruno, E., Castelli, L., Mulè, A., Chiorazzo, M., Ricceri, A., Erzegovesi, S., Caumo, A., Roveda, E., & Esposito, F. (2020). Binge Eating Disorder: What Is the Role of Physical Activity Associated with Dietary and Psychological Treatment? Nutrients 2020, Vol. 12, Page 3622, 12(12), 3622. https://doi.org/10.3390/NU12123622

- de Sousa, M. S. S. R., dos Reis, V. M. M., Novaes, J. da S., de Sousa, J. M., & de Souza, D. M. (2014). Effects of resistance training on binge eating, body composition and blood variables in type II diabetics. Acta Scientiarum – Health Sciences, 36(1), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.4025/ACTASCIHEALTHSCI.V36I1.18048

- M D Levine, M D Marcus, & P Moulton. (n.d.). Exercise in the treatment of binge eating disorder – PubMed. Retrieved November 16, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8932555/

- Collins, H., Booth, J. N., Duncan, A., Fawkner, S., & Niven, A. (2019). The Effect of Resistance Training Interventions on ‘The Self’ in Youth: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Medicine – Open, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S40798-019-0205-0

- Ciccolo, J. T., Santabarbara, N. J., Dunsiger, S. I., Busch, A. M., & Bartholomew, J. B. (2016). Muscular strength is associated with self-esteem in college men but not women. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(12), 3072–3078. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105315592051

- Burton, A. L., & Abbott, M. J. (2019). Processes and pathways to binge eating: Development of an integrated cognitive and behavioural model of binge eating. Journal of Eating Disorders, 7(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/S40337-019-0248-0/FIGURES/2

- Davy, B. M., Dennis, E. A., Dengo, A. L., Wilson, K. L., & Davy, K. P. (2008). Water Consumption Reduces Energy Intake at a Breakfast Meal in Obese Older Adults. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 108(7), 1236. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JADA.2008.04.013

- Van Walleghen, E. L., Orr, J. S., Gentile, C. L., & Davy, B. M. (2007). Pre-meal Water Consumption Reduces Meal Energy Intake in Older but Not Younger Subjects. Obesity, 15(1), 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1038/OBY.2007.506

- Popkin, B. M., Barclay, D. V., & Nielsen, S. J. (2005). Water and Food Consumption Patterns of U.S. Adults from 1999 to 2001. Obesity Research, 13(12), 2146–2152. https://doi.org/10.1038/OBY.2005.266

- Stroebele, N., & De Castro, J. M. (2004). Television viewing is associated with an increase in meal frequency in humans. Appetite, 42(1), 111–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2003.09.001

- T D Spagnoli, L Bioletti, C Bo, & M Formigatti. (n.d.). [TV, overweight and nutritional surveillance. Ads content, food intake and physical activity] – PubMed. Retrieved November 16, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14969315/

- Nelson, J. B. (2017). Mindful Eating: The Art of Presence While You Eat. Diabetes Spectrum : A Publication of the American Diabetes Association, 30(3), 171. https://doi.org/10.2337/DS17-0015

- O’Reilly, G. A., Cook, L., Spruijt-Metz, D., & Black, D. S. (2014). Mindfulness-based interventions for obesity-related eating behaviours: a literature review. Obesity Reviews : An Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 15(6), 453–461. https://doi.org/10.1111/OBR.12156

- Woolhouse, H., Knowles, A., & Crafti, N. (2012). Adding mindfulness to CBT programs for binge eating: a mixed-methods evaluation. Eating Disorders, 20(4), 321–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2012.691791

- Katterman, S. N., Kleinman, B. M., Hood, M. M., Nackers, L. M., & Corsica, J. A. (2014). Mindfulness meditation as an intervention for binge eating, emotional eating, and weight loss: a systematic review. Eating Behaviors, 15(2), 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EATBEH.2014.01.005

- Goossens, L., Braet, C., & Decaluwé, V. (2007). Loss of control over eating in obese youngsters. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BRAT.2006.01.006

- Jenkins, J. S. (2001). The Mozart effect. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 94(4), 170. https://doi.org/10.1177/014107680109400404

- Jensen, K. L. (2001). The effects of selected classical music on self-disclosure. Journal of Music Therapy, 38(1), 2–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/JMT/38.1.2

- Chafin, S., Roy, M., Gerin, W., & Christenfeld, N. (2004). Music can facilitate blood pressure recovery from stress. British Journal of Health Psychology, 9(Pt 3), 393–403. https://doi.org/10.1348/1359107041557020

- Siedliecki, S. L., & Good, M. (2006). Effect of music on power, pain, depression and disability. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 54(5), 553–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1365-2648.2006.03860.X

- Hanser, S. B., & Thompson, L. W. (1994). Effects of a music therapy strategy on depressed older adults. Journal of Gerontology, 49(6). https://doi.org/10.1093/GERONJ/49.6.P265

- Scheufele, P. M. (2000). Effects of Progressive Relaxation and Classical Music on Measurements of Attention, Relaxation, and Stress Responses. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 2000 23:2, 23(2), 207–228. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005542121935

- Boukes, M., & Vliegenthart, R. (2017). News consumption and its unpleasant side effect: Studying the effect of hard and soft news exposure on mental well-being over time. Journal of Media Psychology, 29(3), 137–147. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/A000224

- de Hoog, N., & Verboon, P. (2020). Is the news making us unhappy? The influence of daily news exposure on emotional states. British Journal of Psychology (London, England : 1953), 111(2), 157–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/BJOP.12389

- Thomée, S., Härenstam, A., & Hagberg, M. (2011). Mobile phone use and stress, sleep disturbances, and symptoms of depression among young adults – A prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-66/TABLES/4

- Lepp, A., Barkley, J. E., & Karpinski, A. C. (2014). The relationship between cell phone use, academic performance, anxiety, and Satisfaction with Life in college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 31(1), 343–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHB.2013.10.049

- van Harmelen, A. L., Gibson, J. L., St Clair, M. C., Owens, M., Brodbeck, J., Dunn, V., Lewis, G., Croudace, T., Jones, P. B., Kievit, R. A., & Goodyer, I. M. (2016). Friendships and Family Support Reduce Subsequent Depressive Symptoms in At-Risk Adolescents. PLOS ONE, 11(5), e0153715. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0153715

- Ozbay, F., Johnson, D. C., Dimoulas, E., C.A. Morgan, I., Charney, D., & Southwick, S. (2007). Social Support and Resilience to Stress: From Neurobiology to Clinical Practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont), 4(5), 35. /pmc/articles/PMC2921311/

- King, A. R., Russell, T., & Veith, A. C. (2016). Friendship and Mental Health Functioning. https://commons.und.edu/psych-fac

- Thirthalli, J., Naveen, G. H., Rao, M. G., Varambally, S., Christopher, R., & Gangadhar, B. N. (2013). Cortisol and antidepressant effects of yoga. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 55(Suppl 3), S405. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.116315

- Vedamurthachar, A., Janakiramaiah, N., Hegde, J. M., Shetty, T. K., Subbakrishna, D. K., Sureshbabu, S. V., & Gangadhar, B. N. (2006). Antidepressant efficacy and hormonal effects of Sudarshana Kriya Yoga (SKY) in alcohol dependent individuals. Journal of Affective Disorders, 94(1–3), 249–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JAD.2006.04.025

- McIver, S., O’Halloran, P., & McGartland, M. (2009). Yoga as a treatment for binge eating disorder: a preliminary study. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 17(4), 196–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CTIM.2009.05.002

- Weigle, D. S., Breen, P. A., Matthys, C. C., Callahan, H. S., Meeuws, K. E., Burden, V. R., & Purnell, J. Q. (2005). A high-protein diet induces sustained reductions in appetite, ad libitum caloric intake, and body weight despite compensatory changes in diurnal plasma leptin and ghrelin concentrations. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 82(1), 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN.82.1.41

- Lejeune, M. P. G. M., Westerterp, K. R., Adam, T. C. M., Luscombe-Marsh, N. D., & Westerterp-Plantenga, M. S. (2006). Ghrelin and glucagon-like peptide 1 concentrations, 24-h satiety, and energy and substrate metabolism during a high-protein diet and measured in a respiration chamber. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 83(1), 89–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/83.1.89

- Westerterp-Plantenga, M. S. (2003). The significance of protein in food intake and body weight regulation. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, 6(6), 635–638. https://doi.org/10.1097/00075197-200311000-00005

- Ortinau, L. C., Hoertel, H. A., Douglas, S. M., & Leidy, H. J. (2014). Effects of high-protein vs. high- fat snacks on appetite control, satiety, and eating initiation in healthy women. Nutrition Journal, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-13-97

- Wohl, M. J. A., Pychyl, T. A., & Bennett, S. H. (2010). I forgive myself, now I can study: How self-forgiveness for procrastinating can reduce future procrastination. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(7), 803–808. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PAID.2010.01.029